By: Allvue Team

March 23, 2023

Although it’s been a part of the investing conversation for decades, interest in private equity is growing faster than ever in terms of committed dollars, successful launches, and headline generation. Our guide to investing in private equity breaks down the process, identifies the players, and explains how to evaluate private equity software.

What is private equity?

Private equity is the process of taking an ownership stake in a company with the goal of adding value (both monetary and through experience and knowledge) and selling it or listing it as an IPO several years later.

Capital has been pouring into private equity (PE) at unprecedented levels, and for good reason: the pool of publicly traded securities has gotten smaller over the past two decades (from roughly 5,500 in 2000 to 4,000 in 2020). As companies move to the private market for greater flexibility — or opt to never go public in the first place — opportunity grows for investors and fund managers within the PE space.

Private equity, defined

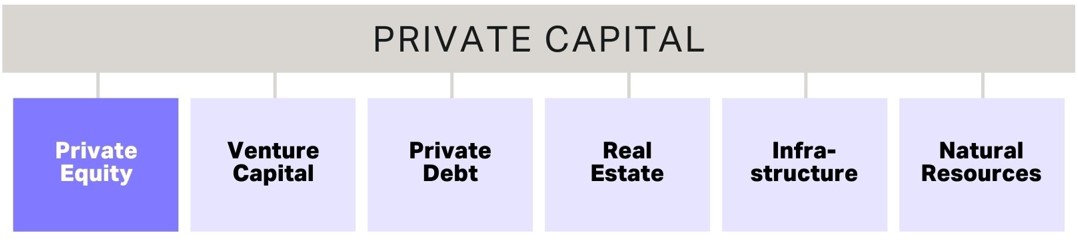

Private equity is a segment of private capital, which is inclusive of all alternative investments not available on public markets such as private debt, natural resources, mezzanine debt, private placement loans, and distressed debt.

The Segments of Private Capital

PE, specifically, is a strategic investment process that involves taking an ownership share in a company or asset, both rising stars and companies that may be struggling but show promise. Contrary to its name, this type of investment can be made in an established public company that is looking to be taken private (e.g. Staples or H.J. Heinz) or a private company with growth potential (e.g. DoorDash or AirBnB).

How long does a private equity fund last?

The long-term goal for PE partners, known as fund managers or general partners (GPs), is to bring value – through funding, expertise, and mentorship – to the companies, foster growth, and execute a (hopefully profitable) sale or IPO several years later (typically no fewer than three and no more than 10 years).

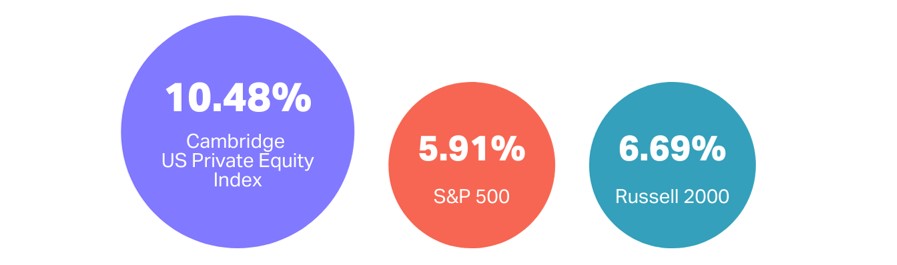

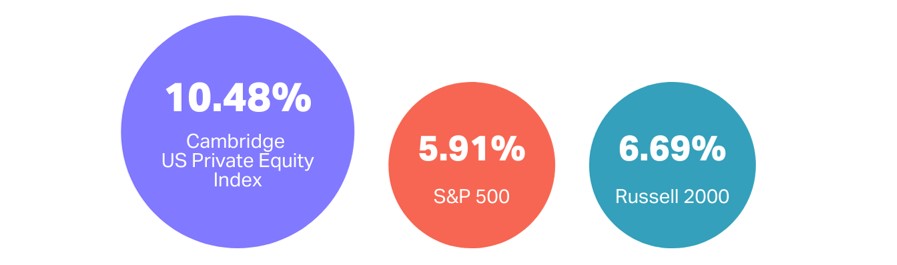

20-Year Average Annual Return

Source: Cambridge Associates

The results have been profitable; June 2020 findings from revealed that its

READ MORE: 4 Steps Emerging Private Equity & Venture Capital Firms Can Take to Accelerate Growth

A brief history of private equity

The modern PE strategy was theoretically born in 1901, when J.P. Morgan orchestrated what’s considered the first leveraged buyout of Carnegie Steel for $480 million. In 1946, the first true private equity firms, American Research and Development Company and J.H. Whitney, hung their respective shingles.

But the practice didn’t truly take off until the 1970s and 1980s, when fledgling technology companies including Apple and Intel used the venture capital avenue to acquire funding. Additionally, institutional investors began investing in private companies and one of the most well-known leveraged buyouts (of RJR Nabisco, for nearly $25 billion) made headlines.

The industry endured some ups and downs in the 1990s and early 2000s, amid the tech boom (and eventual bust). By 2003, the PE sector was ready for a new renaissance and the environment was a perfect storm for this reinvigorated industry. Historically low interest rates, reduced lending standards, and increased regulation for public companies made some buyout offers (including ones for Hertz, Harrah’s, and Alliance Boots) impossible to refuse.

In 2006, the PE industry raised $401 billion, easily topping previous records.

“Essentially a revamped version of the leveraged buyout firms of the 1980s, these firms buy undervalued or underappreciated companies, fix them up and sell them for a fast profit, sometimes in as little as three years.”

-“Private equity firms spin off cash,” March 16, 2006, USA Today

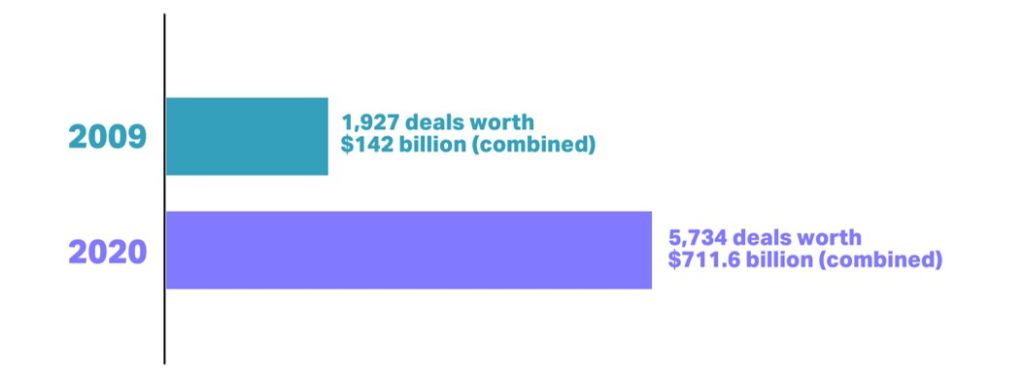

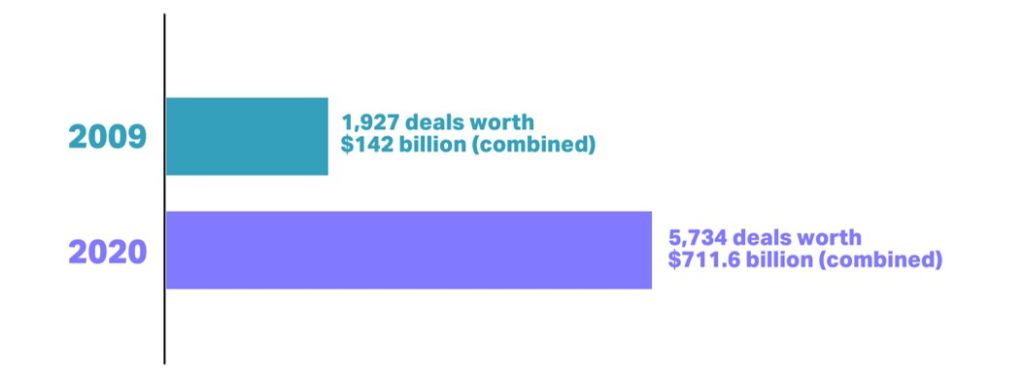

Over the last decade-plus, the industry has grown in terms of both dollars and deals:

Growth of Private Equity Industry

Sources: 2009 data – PitchBook, 2020 data – Institutional Investor

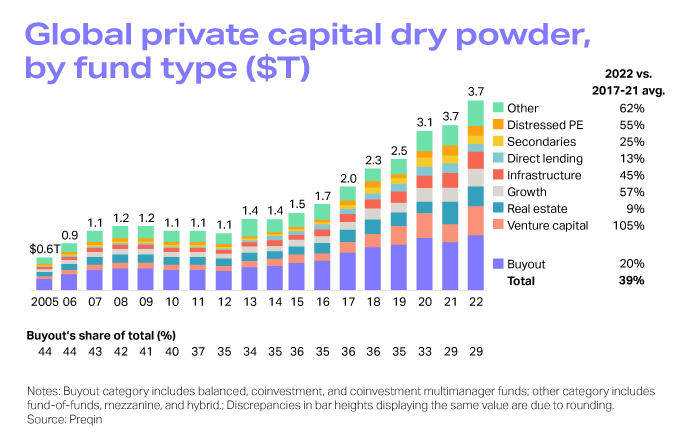

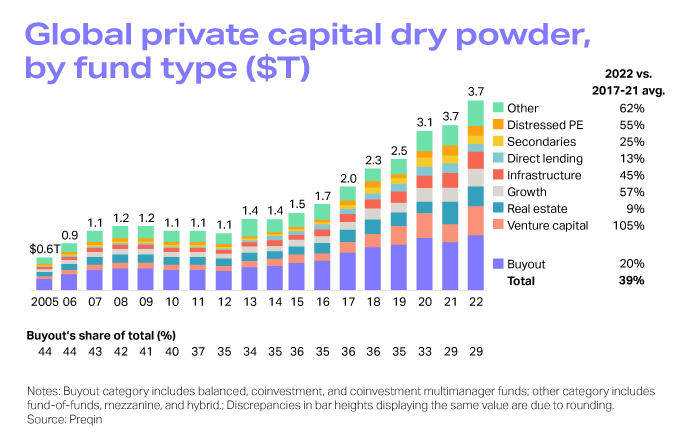

Private equity’s resurgence in the last 10 years is partially due to the financial crisis, which made banks more risk-averse and companies more reliant on alternative funding opportunities. At the same time, PE firms have become flush with capital and looking for where to spend it. Global private equity dry powder levels closed out 2022 with a new all-time high of $3.7 trillion.

READ MORE: HISTORICALLY HIGH PE DRY POWDER SUSTAINS AMID NEW MARKET OUTLOOK

Types of private equity

In many cases, private equity takes the form of a leveraged buyout, where a firm takes ownership of an underlying company that needs additional capital and expertise to grow. In the cases of distressed funding, a firm invests in a listed or unlisted company going through a challenge or hardship and makes improvements before selling. The ultimate goal for both strategies is to sell at a profit or take the company public.

Rarely, private equity investments may include real estate (office buildings, commercial space, apartment complexes) or infrastructure (physical assets such as toll roads, energy assets, and airports).

Venture capital (VC) is a type of private equity, but the two are not synonymous. While the strategies seek the same goal, there are also key differences:

| Venture Capital |

Private Equity |

| Smaller investments (typically capped at $10M) in startups with high growth potential |

Investments of $100M or more in startups and mature companies seeking funds to improve performance |

| Focus on emerging tech and other fields during their infancy |

Focus on more traditional/established industries |

| Invest in the equity of new firms |

Invest via equity and debt securities offered by the company |

Who invests in private equity funds?

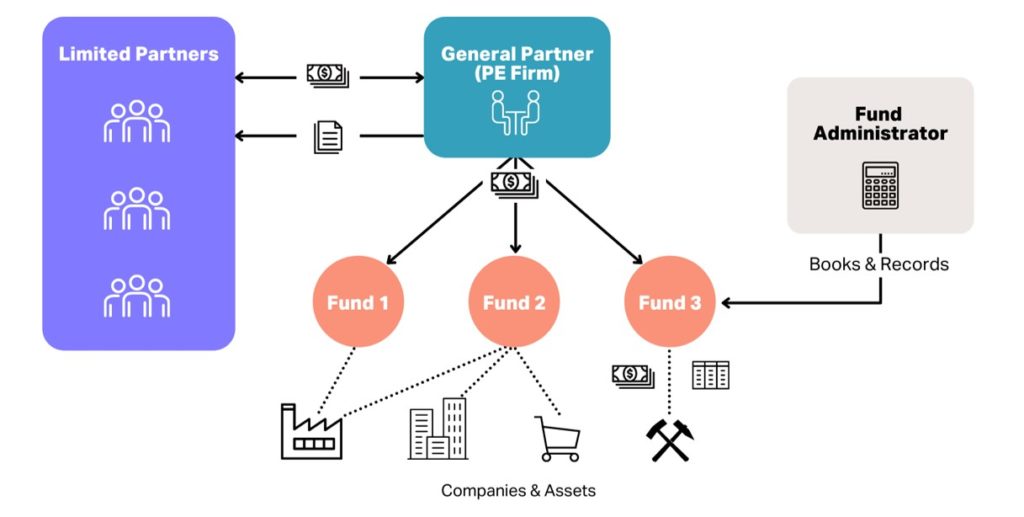

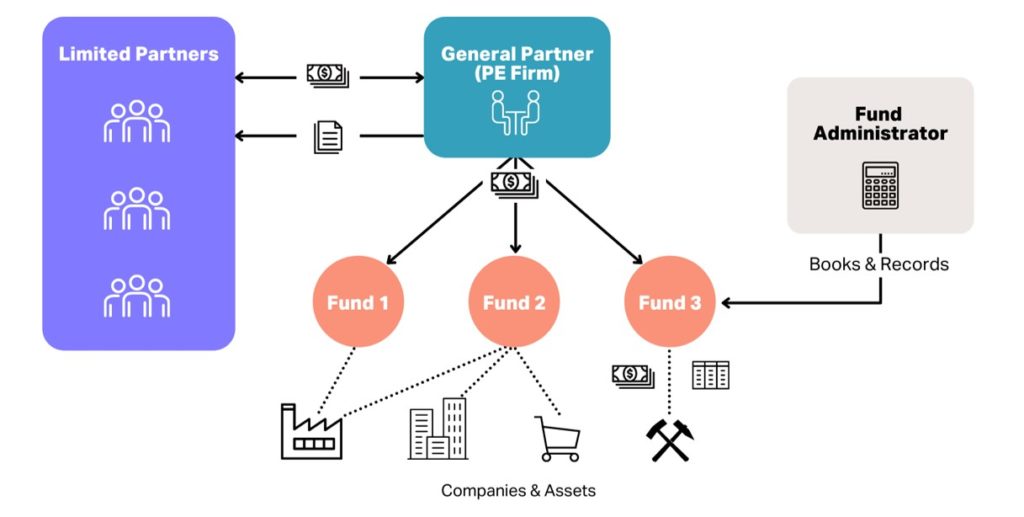

A private equity fund raises its investment capital from limited partners (LPs), who contribute funds and accept limited risk in exchange for typically 80% of the proceeds when the company makes its public debut or gets sold.

This investor class generally includes institutions such as family offices, endowments and foundations, fund of funds, insurance companies, and pension funds.

Private Equity Investment Relationships

Ultra-high-net-worth individual investors also invest in private equity. In fact, private equity holdings comprise more than half (54%) of the alternative investment allocations made by those with a net worth of at least $30 million. The cost of admission over the course of the investment can generally range from $250,000 to $25 million (for the largest funds).

Additionally, the SEC has updated the definition of “accredited investor” beyond monetary threshold to include those with professional certifications, effectively widening the net of potential PE investors.

DOWNLOAD NOW: 80+ PRIVATE EQUITY KPIS

Individual investors wanting exposure to private equity without the minimum threshold can consider b stock in publicly traded private equity firms — like Blackstone Group or KKR & Co. – or an ETF that tracks companies in this niche sector.

How do private equity funds work?

There are nearly 7,000 active PE firms globally managing PE funds, according to McKinsey. Whether they’re overseeing one company or a portfolio of dozens, all strive for the same long-term opportunity: invest, add value, and sell (or take public) for a profit.

This process has five general stages, some of which may happen in parallel:

| Year 0 |

Organization / Formation

|

GPs meet with LPs to explain their vision for the fund (such as targeted regions and investment types). During these conversations, GPs gauge interest and receive capital commitments to the fund from the LPs who are interested. GPs also begin market research on potentially attractive privately held companies. |

Years 0 – 2

|

Fundraising

|

GPs narrow down the investment opportunities and make “capital calls” to collect the initial round of pledged money from investors. (Note: LPs will invest different amounts and will therefore own different percentages of the fund. Depending on the type of LP, they may have different tax implications or investment requirements. These nuances make private equity fund accounting a critical process for GPs to master.) |

Years 1 – 4

|

Deal Sourcing & Investing

|

GPs invest the cash in the identified opportunities and begin to work with the companies on measures that can improve efficiency and bolster cash flow. |

Years 2 – 7

|

Portfolio Management

|

GPs continue to oversee the progress of their investments, making adjustments and liquidations as needed. |

Years 3 – 10

|

Exiting Investments

|

Investments are sold and gains are realized before, ideally, profits are returned to the LPs. LPs typically receive 80% of the proceeds while GPs earn 20% in exchange for their management efforts and acceptance of full liability. |

READ MORE: Understanding Private Equity Fund Accounting

Advantages of investing in private equity

Investing in private equity has several advantages, including but not limited to:

Diversification: By definition, private equity investing offers an opportunity that is not available to the public and is therefore not subject to the volatile “noise” that’s often present in the day-to-day market.

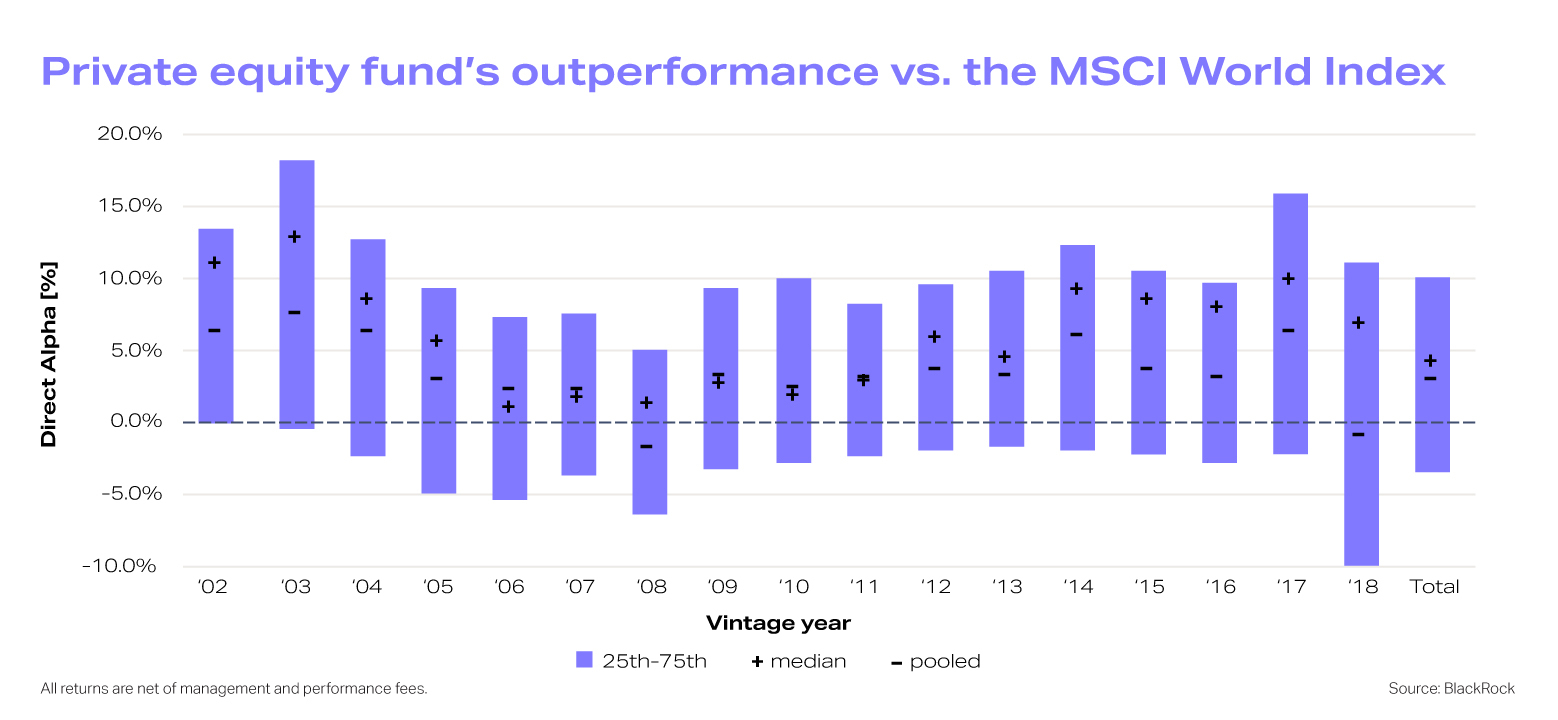

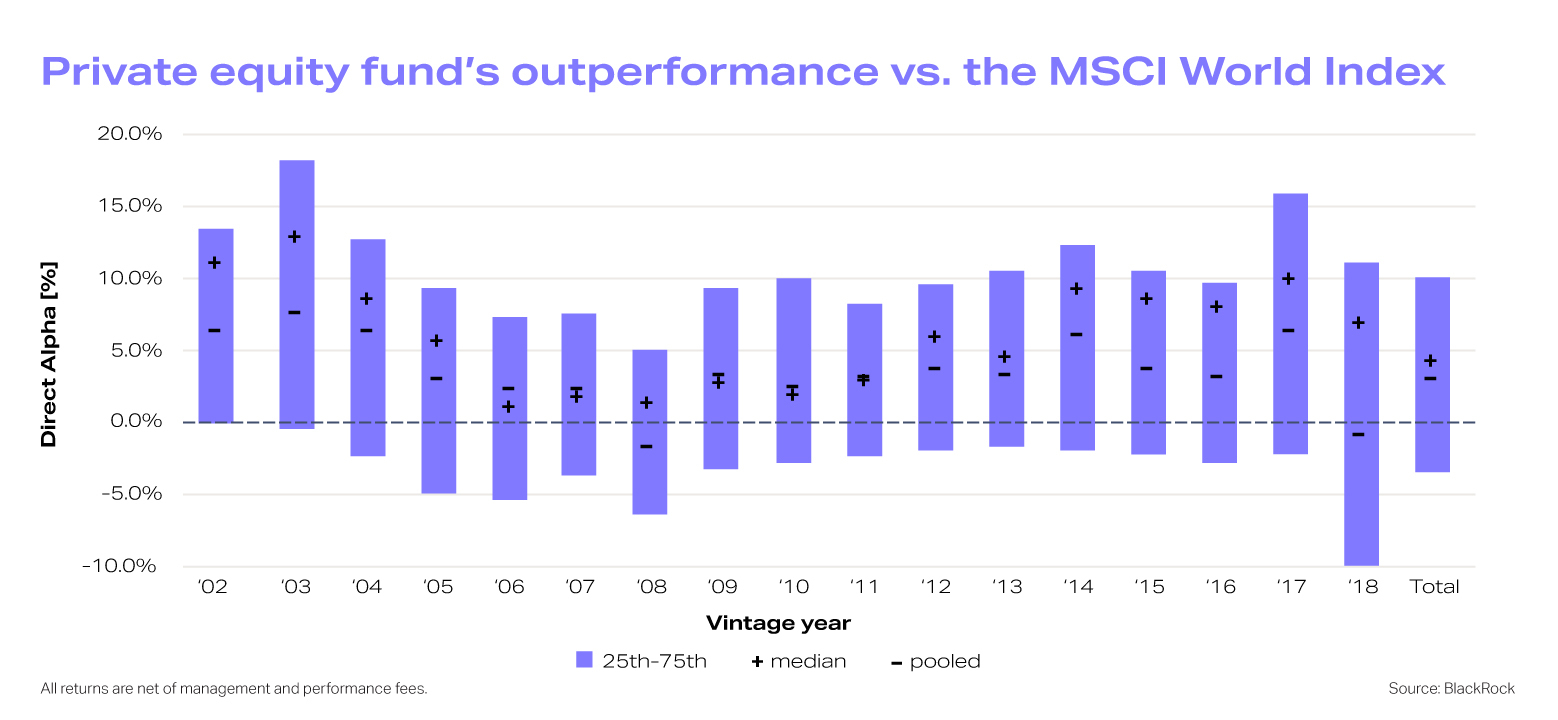

Outperformance: Good things come to those who wait. As cited above, PE strategies have outperformed broader-market indexes over the last 20 years.

Participation: Investing in private equity can be a thrill if your GP is prescient enough to have found the next unicorn. Getting in on the ground floor of something innovative or unique is a priceless experience for some investors.

Risks of investing in private equity

All asset classes have disadvantages and risks; private equity is no different. And some of the factors that make PE appealing (the long investment cycle and the expertise of the fund managers) have a potential disadvantage, as well.

Illiquidity: Because of the long cycle required for a successful PE strategy, an investor’s funds will be tied up for at least 3 years, and typically more.

High barrier to entry: Most PE firms have a minimum requirement that is out of reach for anyone other than ultra-high-net-worth investors or institutions.

Blind pool: Unlike companies trading publicly, PE investments are often hard to research, and in the early stages of financial commitment, they aren’t even determined. This requires a leap of faith for LPs relying on GP to select the assets.

Lack of transparency: As of 2012, PE funds themselves must disclose certain facts to the SEC (such as AUM and potential conflicts of interest). However, these reports are far less detailed than those of publicly traded companies or mutual funds and are not available publicly.

Risk of default: While the potential reward when investing in PE is alluring, the risk of investment default is also high – 2.5 times higher than publicly traded companies.

How software can help GPs manage private equity investments

Investing in private equity presents another challenge for fund managers: complexity in data management and reporting. Manually driven solutions such as Excel, while sufficient for more straightforward data management, create operational risk in the alternatives world regarding version control, possible human error, and the potentially insecure transfer of data.

Fortunately, Allvue has developed customizable solutions designed to help PE firms collate, analyze, and distribute data so teams can feel confident that they’re working with the same information. In addition, the software suite can streamline back-office processes – including capital calls and rebalancing – and reduce the risk of manual error, while also freeing up your employees’ time.

For emerging PE firms hoping to offer the same level of service as their larger counterparts, scalable private equity software solutions and accounting systems can offer the needed sophistication and flexibility that helps them compete despite limited resources.

READ MORE: WHY SPREADSHEETS FAIL: EXCEL ERRORS CAN BE FATAL TO FUNDS

Learn how Allvue’s robust and flexible set of private equity investing solutions can arm GPs with unparalleled investment intelligence.